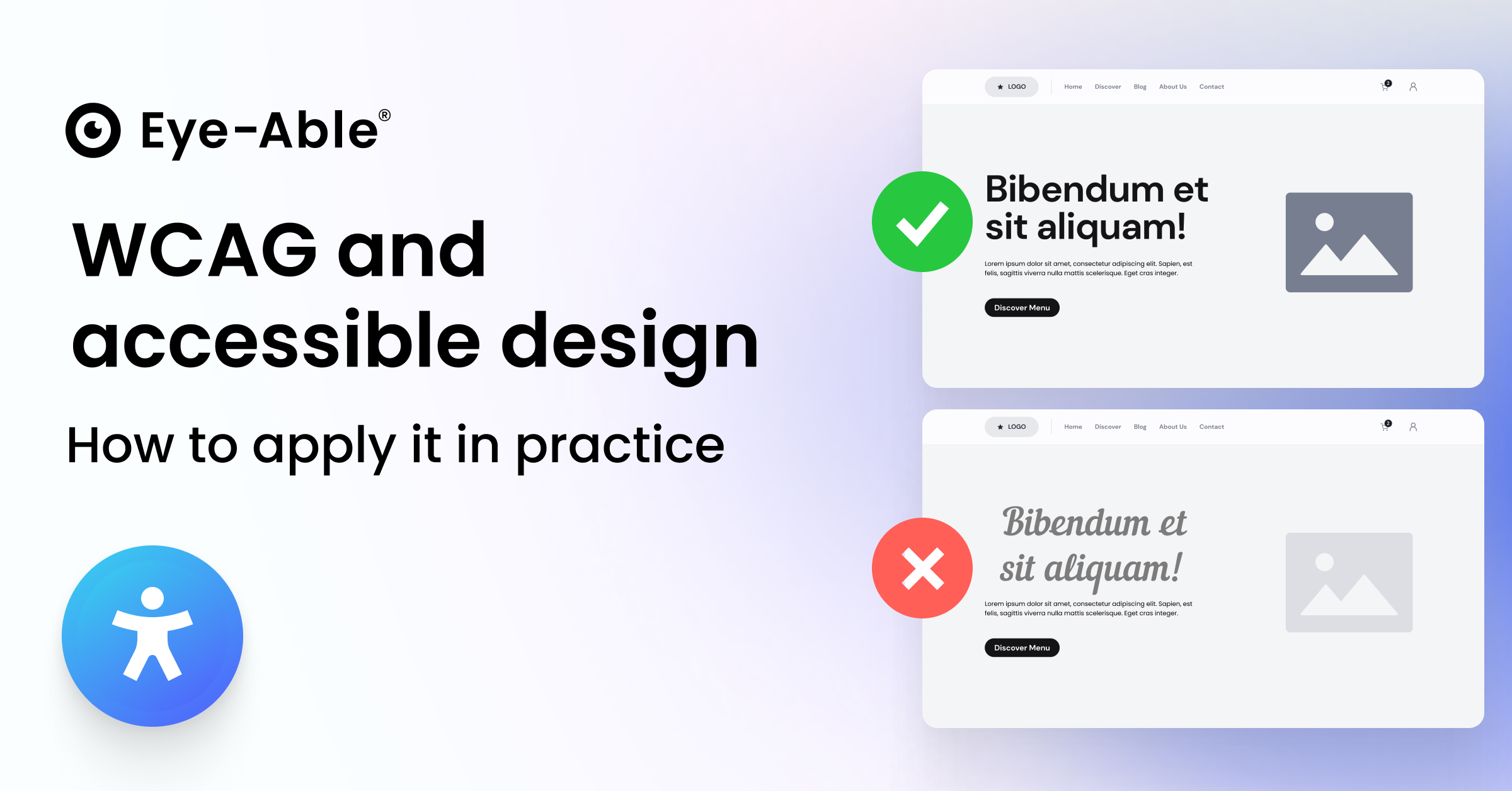

WCAG and accessible design – How to apply it in practice

WCAG and accessible design – How to apply it in practice

Imagine you want to buy a train ticket online. But the text is so small it’s barely legible, the buttons have poor contrast, and important information is conveyed by colour alone. For many people with visual impairments or cognitive limitations, that’s a real barrier.

This is exactly where accessible design comes in: designing content so that it can be understood and used by everyone.

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) provide the international standard for doing just that. They show how colour, typography, layout and interaction can be designed inclusively.

Companies that apply these principles not only create a better user experience, but also reach new audiences and expand their digital visibility.

What is accessible design?

Accessible design covers all design aspects that ensure digital and physical content can be used by people with different abilities and limitations.

A legible typeface and sufficient contrast, for example, benefit not only people with visual impairments but also older users or those in bright environments.

It’s based on the four core WCAG principles:

Perceivable, Operable, Understandable and Robust.

The advantages go far beyond people with disabilities. Accessible design improves usability for everyone, increases the reach of your content and can even have a positive impact on search engine optimisation.

Legal foundations

Barrierefreiheitsstärkungsgesetz (BFSG)

The Barrierefreiheitsstärkungsgesetz (BFSG) translates the European Accessibility Act (EAA) into German law. It obliges companies to design their digital products and services to be accessible.

The regulation particularly affects online shops, banking websites, travel portals and digital health services.

The EN 301 549 standard serves as the technical framework, referring to the WCAG 2.1 as the minimum standard for digital accessibility.

WCAG as the standard for accessible design

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.2, published in December 2024, expand the previous version by nine new success criteria.

They define three levels of compliance:

Level A: Basic requirements

Level AA: Recommended standard for most digital products

Level AAA: The highest level of accessibility

For compliance with the BFSG, Level AA is generally sufficient and practical to implement.

Key contrast requirements under WCAG 2.2

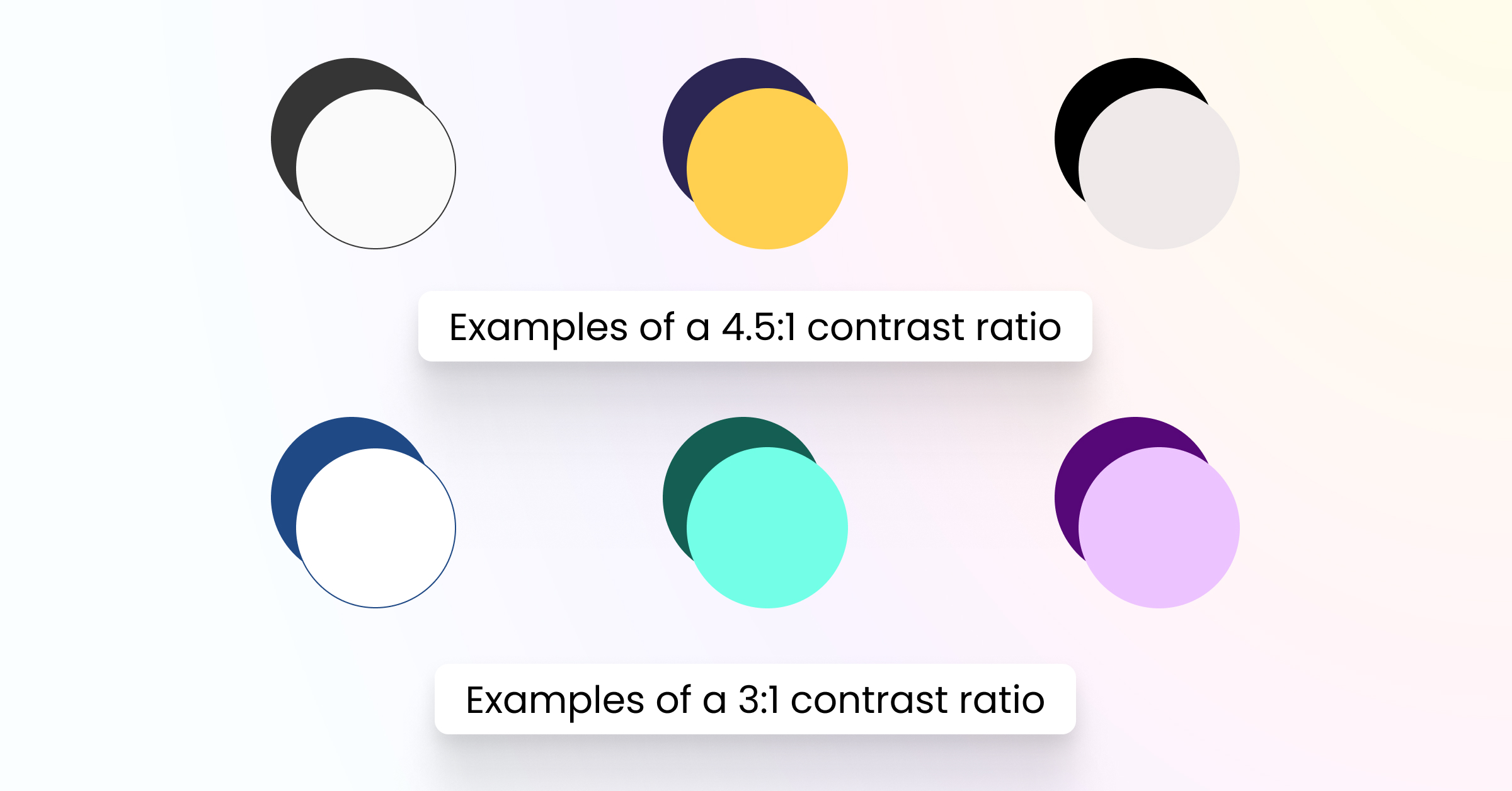

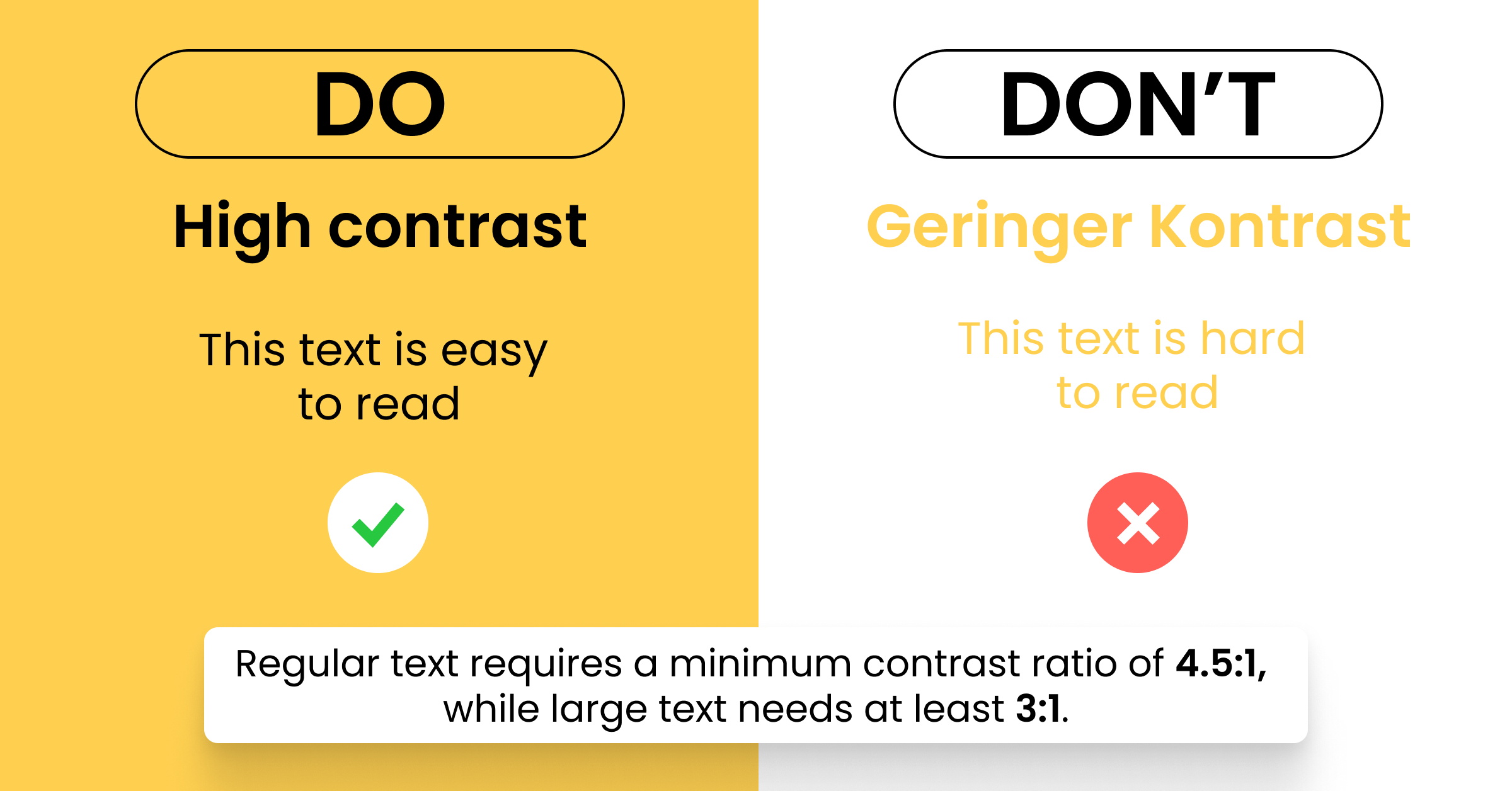

For normal text, the minimum contrast ratio required is 4.5:1 for Level AA compliance, and it increases to 7:1 for the stricter Level AAA compliance.

For large text, defined as text that is 24 pixels or larger, or 19 pixels and bold, the requirements are slightly lower. The minimum contrast ratio is 3:1 for Level AA and 4.5:1 for Level AAA.

Finally, for graphical user interface (GUI) elements, there is no specific minimum ratio required for Level AA (indicated by the dash). However, Level AAA requires a minimum contrast ratio of 3:1.

Standards in print & document design

The DIN 1450 standard defines the criteria for font legibility, taking into account demographic change and the needs of people with visual impairments.

For accessible PDFs, structural tags, a logical reading order and alternative text descriptions are essential.

In print design, DIN 1450 recommends humanist serif typefaces such as Garamond or Sabon Next, which are particularly easy to read for longer texts.

Do’s & don’ts of accessible design

Language and text

Do:

Use clear, simple language and avoid long, complex sentences

Structure your text logically with meaningful headings

Choose inclusive, gender-sensitive wording

Keep paragraphs short and sentences concise

Don’t:

Use complicated jargon without explanation

Use gender-exclusive language

Write overly complex or nested sentencesTypografie & Lesbarkeit

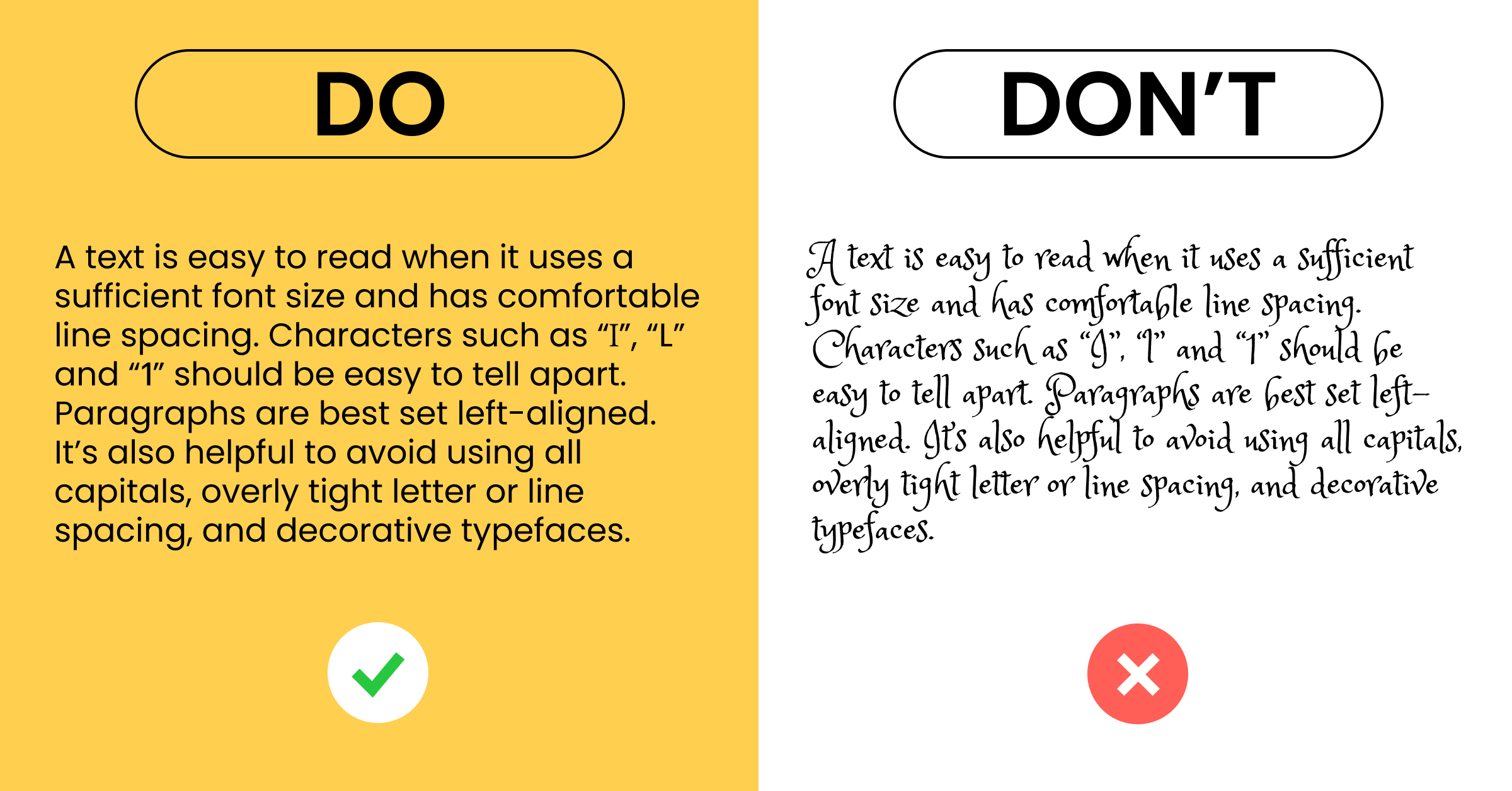

Typography & readability

There is no single “accessible font” — accessibility depends on various factors such as x-height, character distinction, font size and spacing.

Proven, easy-to-read typefaces include Inter, Roboto, Open Sans, Verdana and Arial.

For special requirements, Neue Frutiger 1450 is recommended by DIN 1450.

Do:

Use a minimum font size of 14–16 px for body text

Set the line spacing to at least 1.5 times the font size

Use left-aligned, ragged-right text for better readability

Don’t:

Write long passages in all caps

Use centred alignment for long text blocks

Choose small font sizes or fonts with low legibility

Use serif typefaces on screens (except in specific contexts)

Colours & contrast

Colour contrast plays a crucial role in readability.

The WCAG 2.2 defines clear minimum requirements, which can easily be checked using tools such as the WebAIM Contrast Checker or Colour Contrast Analyser.

Do:

Ensure a contrast ratio of at least 4.5 : 1 for normal text

Use strong contrasts between text and background

Provide additional visual cues (such as icons or patterns) instead of relying on colour alone

Don’t:

Use red–green combinations for important information

Communicate information through colour alone

Choose weak contrasts such as light grey on white

Layout & spacing

A clear, well-structured layout is key to accessibility. Visual order helps users process information more easily and navigate intuitively.

Do:

Use consistent grid structures to guide the eye

Provide generous white space to avoid clutter

Reduce cognitive load through clear visual hierarchies

Keep navigation and interactive elements consistent across all pages

Don’t:

Create overloaded layouts with too many visual elements

Ignore visual hierarchy in headings and spacing

Place navigation elements inconsistently on different pages

Images & media

Alternative text (alt text) is essential for people with visual impairments.

It should describe the content and function of an image precisely and meaningfully.

The rule of thumb: “As short as possible, as long as necessary.”

Do:

Provide descriptive alt text for all images

Use inclusive and diverse imagery

Add captions and transcripts for videos

Offer descriptions for complex graphics or infographics

Don’t:

Leave alt text empty or use meaningless labels such as “image1.jpg”

Place text on busy or patterned backgrounds

Publish videos without subtitles or audio descriptions

Tables & infographics

Tables and infographics must be structured clearly so that assistive technologies, such as screen readers, can interpret them correctly. This ensures that complex information remains accessible to everyone.

Do:

Use a clear table structure with defined header rows and columns

Add labels that can be recognised by screen readers

Maintain a logical reading order

Provide text descriptions for complex data visualisations

Don’t:

Use nested tables without a clear structure

Omit column or row headings

Use layout tables purely for visual design purposes

Digital vs. print media

Accessible design should always be considered across all media.

Digital content needs to be responsive and optimised for various devices and screen sizes.

For PDF documents, structural tags and a logical reading order are indispensable. These elements allow assistive technologies to interpret the content correctly and provide a smooth reading experience for all users.

Accessible design in practice

Putting accessible design into practice requires both technical know-how and an understanding of users’ needs.

Interactive elements such as navigation menus, forms and buttons must be fully operable via keyboard. The Tab key should allow users to move through the page in a logical, predictable order.

When it comes to forms, clear labels, understandable error messages and easy correction options are essential.

Buttons should have meaningful labels and adequate touch targets (at least 44 × 44 pixels).

Testing approaches

Automated testing with tools such as axe DevTools or WAVE

Manual testing using screen readers and keyboard navigation

User testing involving people who rely on assistive technologies

Regular audits with accessibility platforms such as Eye-Able

Common mistakes in design & accessibility

A frequent mistake is focusing solely on visual design without considering usability for all users.

Many designers only think about accessibility after a project is completed, rather than integrating it from the start.

Typical problems

One-off adjustments without continuous monitoring

Lack of involvement of people with disabilities in the design process

Insufficient training for design and development teams

Neglecting accessibility in agile workflows and sprints

Conclusion

Accessible design is not a one-off project, but a continuous process that must be considered in every stage of design and development.

Investing in accessibility not only ensures legal compliance, but also creates better user experiences for everyone and opens the door to new audiences.

With the introduction of the BFSG, accessible design has become a legal requirement – but it should also be seen as an opportunity to make digital products usable and enjoyable for all people.

Eye-Able offers a comprehensive platform for analysing, implementing and continuously monitoring digital accessibility, helping organisations stay compliant and inclusive in the long term.

FAQ on accessible design

What is the difference between accessible design and accessible web design?

Accessible design is a broader concept that includes all design aspects — both digital and physical.

Accessible web design, on the other hand, focuses specifically on websites and web applications.

What is an accessible format?

An accessible format allows people with different abilities to perceive and understand content without barriers.

Examples include:

Structured PDFs with proper tagging

HTML with semantic markup and ARIA attributes

Videos with subtitles or transcripts

What is meant by universal design?

Universal design is a concept in which products and environments are created so that they can be used by as many people as possible, without the need for further adaptation.

It goes beyond accessibility, taking the diversity of human abilities into account from the very beginning.

See how accessible your website design is – simply use the free Eye-Able Accessibility Check.

)